“You are the population of the earth, and we need you to save this world from misery”.

A quote from the little booklet handed out as I last Friday entered Signa Sørensen production “Seven Tales of Misery”. And a pretty bold one too. Almost as vulgar as naïve. But from her other productions “Nika is Dead” and “57 beds” I knew that if someone can come up with a plausible solution to such complex questions, she is it. Her productions are.

Entering “Seven tales of Misery” ment a cleansing ritual, being greeted and instructed by a leader: That there would be rules to follow tonight, there was The Law, and would we go by The Law (all that is above is the same as all that is below), we would indeed contribute to free the world of misery. And in a metaphorical setting I for one wanted that: I want to contribute.

Then at the wardrobe, we exchanged our coats for hooded capers, and were lead into the Great Hall where further instructions were given. We would do no less than travel the globe in a matter of hours.

The sense of being part of something bigger, or at least someone trying to do something bigger than life, was immense. The hooded caper disintegrated to a certain degree the identity, the gender and the sense of direction, why most people happily for the first part of the play, followed their leader. But what really drew my attention was that the apparent absence gender and identity, added an immense feeling of an almost ontological presence. We were in this together. Alike.

Then after being led by a Leader (every leader had first name starting with the letter A), I started getting somewhat annoyed, because from her earlier works I knew they really could take off once you throw yourself into them. I got annoyed by the crowd, I got annoyed by the success, the turnout, because I couldn’t move freely, I could not move at will, I had surrendered to The Law of being led.

But then as we crossed the imaginary continents, and met The Refugees, Lady Asia and Lady Arabia and many other of the central players, the resemblance was clear. We were indeed the population of earth, and the more audience they could stuff in that theater, the more real, the more dynamic the thing would have become.

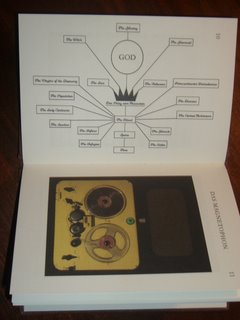

Then slowly as we passed through an impressive consistant scenography, the presence of Der Prince became more and more lucid. Der Prince who had the ability to collect and erase the world of all misery.

And that’s when things started to get really edgy. The construction under which Der Prince could promise to erase misery ; There were only unconditional surrender, there would have to be great sacrifice, and there could be only one love: The love of God.

I felt trapped. It was somewhat like watching a nightmare unfold. There is less escaperoom than there is will to escape. Der Prince then ultimately performed a ritual during which he proclaimed that his mission was almost done, that he had in fact collected the misery of this world, and that it was time for him to leave, which was also a promise of the new Era to Begin.

I left and we left. Not wanting to leave, really. There were parts of the world I didn’t get to see, and misery I didn’t get of my chest, and inbalance where I could have contributed with balance. But we left because it was a play, a production. A production of impressive proportions and spot on precision.

The description of the play should rightfully be longer or not even there. What stands out more important is that here is someone, a director and a dedicated crowd, that have taken a giant leap forward in the world of theater, in the world of arts, and to be honest, here is one of the most competent, sensible and hard hitting contributions to the discussion and perception of the contemporary state of modernity.

All in all very courageous move.

October 02, 2006

Subscribe to:

Comment Feed (RSS)

|